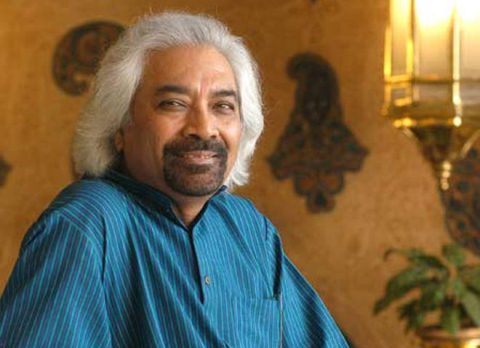

By Sam Pitroda

Today it is widely recognised that the 21st Century will be driven by knowledge, and a nation’s competitive advantage in the global economy will be sustained by a focused and innovative education agenda. To meet the challenges of this century, India needs to usher in a knowledge revolution that seeks to bring about systemic changes in the education and knowledge structures of the country.

Reform in the education system is critical for meeting the challenges posed by demography, disparity and development, and for creating an empowered generation for the future.

While our economy has made significant strides, the education system has not kept pace with the aspirations of the 550 million below the age of 25, a demographic that has the potential to constitute one-fourth of the global workforce by 2020. Consequently, we have not been able to harness our greatest asset?our human resource.

To leverage this asset, a focused education and skill development agenda is needed that provides innovative solutions to our current challenges. The vast disparity in the country today is a result of skewed access to knowledge. To address this, we need a substantial expansion in educational opportunities, with a special emphasis on inclusion so that nobody is left out of the system. Finally, to accelerate the course of sustainable development in the country, efforts have to be undertaken to create an educational system that nourishes innovation, entrepreneurship and addresses the skill requirements of a growing economy.

To initiate this process of reform, the government needs a focused agenda to address the concerns of the school, vocational and higher education streams. We need to bring about a paradigm shift in our education systems with the perspective of enhancing access and employability, and generating long-term qualitative changes that enable us to compete in the global knowledge economy.

At the bottom of the knowledge pyramid, steps must be taken to enhance access to quality elementary education, given the low levels of enrolment and high percentage of dropouts at the school level.

This requires a Central legislation affirming the Right to Education. Making access to good school education a reality also requires major expansion at the secondary and elementary levels and generational changes in the school system with emphasis on local autonomy in management of schools, decentralisation and flexibility in disbursal of funds.

Further, the curriculum and examination systems should be overhauled to encourage conceptual understanding of subjects and a move away from an assessment system that rewards rote learning. With English being seen as an important determinant of access to higher education and employment possibilities, English language teaching should be introduced, along with the first language, from Class I.

Also, due emphasis should be placed on teaching subjects such as Maths and Science, which are usually perceived as difficult, in ways that encourage students to take them up. Most importantly, ICT should be leveraged in a big way by students and teachers to supplement learning, and by administrators to facilitate transparency in the system.

Vocational education and training (VET) is an important element of a nation?s education initiative.

There is a growing concern today that the education system is not fulfilling its role of building a pool of skilled and job-ready manpower, resulting in a mismatch between the skill requirements of the market and the skill base of the job seekers. To avail the fruits of our demographic dividend and to strengthen the link between education and employability, we need to overhaul the system of VET in the country.

The focus should be on increasing the flexibility of VET within the mainstream education system by providing due linkages with the school and higher education. This could also be done through community colleges that provide two-year associate degree courses. Further, to effectively provide quality skill development, steps should be taken to expand capacity through innovative delivery models, including robust public-private partnerships. Given that only 7 per cent of the country’s labour force is in the organised sector, training options available for the informal sector should be enhanced. It is also necessary to ensure a robust regulatory and accreditation framework, along with proper certification of vocational education and training to enhance the value of such training.

While primary and vocational education create the base, to be on the cutting edge of innovation and discovery, an excellent system of higher education is critical. Reforms in higher education in India should address the three concerns of Expansion, Excellence and Inclusion. Our current Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) for higher education (percentage of the 18-24 age group enrolled in a higher education institution) is around 10-11 per cent whereas it is 25 per cent for many other developing countries. The quality of education in the higher education sector is also uneven and the system is illequipped to face the challenge of inclusion. There are large disparities in enrolment rates across states, urban and rural areas, sex, caste and poor-non-poor.

These are significant challenges which require huge investments in terms of time, effort and finances. To bring our GER at par with developed nations we need a massive expansion of the system of higher education. This can be brought about by creating new universities and by restructuring the existing ones. Such a quantum jump will have to be well planned and funded. To increase investment in the sector, alternative sources of financing should be tapped, including industry linkages, philanthropic contributions and private participation. To enhance quality in the system, reforms in teaching, faculty, curriculum and governance should be implemented.

Reforms in governance are crucial for creating a new paradigm of regulation which will encourage openness, transparency and remove the cumbersome entry barriers to new institutions. In India, it requires an act of legislature of Parliament to set up a university. The deemed university route is much too difficult for new institutions. The consequence is a steady increase in the average size of existing universities with a steady deterioration in their quality.

Further, as we seek to expand the higher education system, entry norms will be needed for private institutions and public-private partnerships. The institutional framework for this purpose must be put in place here and now. Currently, there is a multiplicity of regulatory bodies in the higher education sector, often with overlapping mandates. The challenge therefore is to design a regulatory system that increases the supply of good institutions and fosters accountability in those institutions. In this context the creation of an Independent Regulatory Authority for Higher Education could be explored. Such a body would be at an arm’s length from all stakeholders and would accord degree granting power to universities.

To ensure that all deserving students have access to higher education, irrespective of their socio-economic background, strategies for inclusion must also be incorporated, including well funded scholarships and affirmative action that takes into account the multi-dimensionality of deprivation.

A strong eco-system of research is critical for India?s transformation into a knowledge and skills economy. Consequently, reform in higher education should also focus on improving the quality of research in the country so that we don’t end up exporting our talent. This reform agenda, though vital, will not be complete unless associated sectors which impact education and learning are also revitalised, including libraries, translation, the IPR regime, knowledge networking, and innovation and entrepreneurship systems in the country. editor@ictpost.com